Vanessa Davey, Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca

29th March 2020

The pace of expansion of the COVID-19 epidemic in Spain has been very fast. Comparative trajectories by country of confirmed cases and deaths show that the country has one of the fastest spreads on record[i].

The health and social care system in Spain is highly devolved. In normal times regional autonomous governments have large organizing, recruiting, buying, supervising and regulating powers, much exceeding those of local authorities in Britain. The central government health and social care responsibilities are more of a coordinating and overseeing nature.

Social care in the community is devolved by the regional autonomous governments to city and municipal councils operating at a local-level, while responsibility for care homes remains with the regional governments. This includes inspecting and setting standards for all care homes, determining the number of publicly-funded places to be contracted per year and fixing prices. Significant differences exist between regions in official standards, including aspects such as the composition of staff and staff to resident ratios[ii]. Care homes are mainly (but not entirely) privately-owned and privately-managed. The majority of private care homes are occupied by both publicly-funded places and private payers, with the latter generally forming a smaller portion of demand.

The care home market in Spain was recently described by business analysts as a “resilient sector”, ripe for merger and acquisition, characterised by high occupancy rates, significant unmet demand and a growing elderly population (over 65´s will make up one quarter of the Spanish population within the next 12 years)[iii]. “Principal operators” only represent 17% of the total market[iv] and as yet care homes are evenly distributed by size (Table 1).

Table 1: Care homes in Spain by size

| Beds per care home | <25 places | 26-49 places | 50-99 places | >=100 places | TOTAL |

| Number of care homes | 1147 | 1464 | 1476 | 1208 | 5295 |

| % | 22% | 28% | 28% | 23% | 100% |

Although the Emergency state declared on Saturday 14th of March does nominally return much power to the central government, it is unclear how such powers might be exerted through the pre-existing administrative structures. One area in which coordination and unifying criteria have been lacking up to now is that of reporting COVID cases in care homes. Therefore, the figures collected in table 2 updated to 26/03/20 are obtained from national media outlet (Cadena SER), can only be taken as broadly orientative.

According to the official data provided by the Spanish Ministry of Health the national death toll reached 4011, by 26th March (Table 2). At this time the unofficially reported deaths of care home residents totaled 1548. If these were distributed evenly among the autonomous regions, they would have accounted for around 38% of deaths per region but as Table 2 shows they are very unevenly distributed, resulting in a median average of 27%. In three regions care resident deaths comprise in excess of half all fatalities in the region from COVID-19. In the Rioja region, that figure reaches 86%.

Table 2: Observed and estimated deaths attributed to COVID-19 by Spanish autonomous region in and outside care homes, up until and including 24th March 2020.

| Autonomous region | Population1 | Official deaths per autonomous region2 | Estimated deaths of care home residents3 | Care home resident deaths as a percentage of all deaths per region | Care home resident deaths as a percentage of care home places per region 4 | Days since first reported case of COVID-19 infection in a member of the general population |

| Andalucía | 8,426,405 | 134 | 51 | 38% | 0.11% | 29 |

| Aragón | 1,320,794 | 48 | 26# | 54% | 0.14% | 28 |

| Asturias | 1,022,293 | 27 | 10 | 37% | 0.07% | 25 |

| Baleares | 1,187,808 | 17 | 1 | 6% | 0.02% | 29 |

| Canarias | 2,207,225 | 24 | 0 | 0% | 0.00% | 29 |

| Cantabria | 581,684 | 17 | 5 | 29% | 0.07% | 25 |

| Castilla y León | 2,408,083 | 202 | 85 | 42% | 0.16% | 28 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 2,035,505 | 243 | 35 | 14% | 0.18% | 25 |

| Catalunya | 7,565,099 | 672 | 150+ | 22% | 0.24% | 31 |

| Extremadura | 1,065,371 | 58 | 16 | 28% | 0.11% | 26 |

| Galicia | 2,700,330 | 32 | 2 | 6% | 0.01% | 24 |

| La Rioja | 313,582 | 43 | 37 | 86% | 1.17% | 26 |

| Madrid | 6,640,705 | 2090 | 1065* | 51% | 2.13% | 31 |

| Murcia | 1,487,698 | 8 | 1 | 13% | 0.03% | 18 |

| Navarra | 653,8465? | 49 | 2 | 4% | 0.03% | 26 |

| País Vasco | 2,178,048 | 180 | 13 | 7% | 0.07% | 26 |

| Valencia | 4,974,475 | 167 | 44 | 26% | 0.16% | 31 |

| TOTAL | 46,115,105 | 4011 | 1543 | 27% | 0.28% | 27 |

1 Comunidades y ciudades autónomas en España. Wikipedia. Available at:

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anexo:Comunidades_y_ciudades_aut%C3%B3nomas_de_Espa%C3%B1a

2 Spanish Ministry of Health.

3 “Drama en las residencias: cientos de ancianos muertos por coronavirus y ya hay 1.600 mayores contagiados.” Cadena SER. Available at: https://cadenaser.com/ser/2020/03/26/sociedad/1585204942_349816.html

4 Date on number of care home places per region taken from above source, except Catalonia. Date for this region is from the source used for Table 1.

#Number of people died in care homes for Argon is an estimate. According to Cadena SER, 40 people have died of Coronavirus in Aragon, “the majority of which were residents of residential/nursing homes”. The estimate assumes 2/3rd of these were residents, equal to 26 people.

+ “Confirmados 150 muertes en residencies geriátricas catalanas por coronavirus” El Independiente, 26 March 2020. https://www.elindependiente.com/politica/2020/03/26/la-generalitat-permitira-sacar-a-ancianos-de-residencias-geriatricas-para-evitar-su-contagio/

This figure refers specifically to deaths of care home residents “within care homes” and may exclude deaths of care home residents transferred to hospital.

*This figure, initially reported by Cadena SER has since been declared official.

In Madrid, the situation has received worldwide alarm following reports of residents being found “dead in their beds” when the military arrived to remove the remains of other deceased residents. The public outcry now ensuing is being responded to by pleas to consider the proportionality of the deaths. In Madrid, representatives from the regional government have underlined that the deaths occurring in care homes since the start of the crisis only represents 2% of the population resident in care homes in Madrid. Approximately one month has passed since the first detected case in Madrid and in that period 1,065 have been registered (some of which are not been confirmed as COVID-19 cases). In March 2019, 1,000 care home residents died of natural causes in Madrid[v].

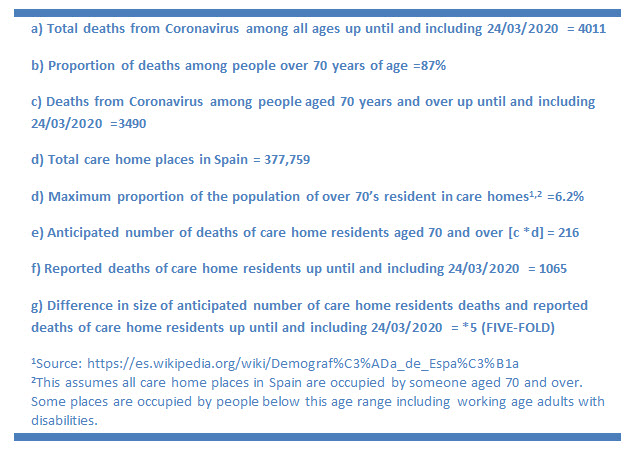

Another way of considering these deaths is by estimating deaths according to the currently observed Coronavirus death rate for older people relative to the potential population of older people in care homes (Figure 1).

We know that in Spain, age is a major factor in COVID-19 mortality risk, with 87% of deaths occurring among people aged 70 and above. Based on the maximum number of places available, care homes in Spain cannot be housing more than 6% of the population of over 70’s (and that is an overestimate, given that care homes also house younger age ranges). If Coronavirus were causing equal numbers of deaths among people living within the community as people resident in care homes, 216 care home resident deaths would have been the anticipated number up until 24th March 2020. The reported number of deaths is almost five times that figure. This suggests that being in a care home is a risk factor for dying from COVID-19 in Spain. It is imperative to underline that the estimate of this increased risk may be reduced by half or more if it were adjusted for the heightened levels of frailty among care home residents –however, a level of increased risk association with care home residence would certainly remain[vi].

Figure 1: Estimation of anticipated deaths of care home residents aged 70 and over in Spain

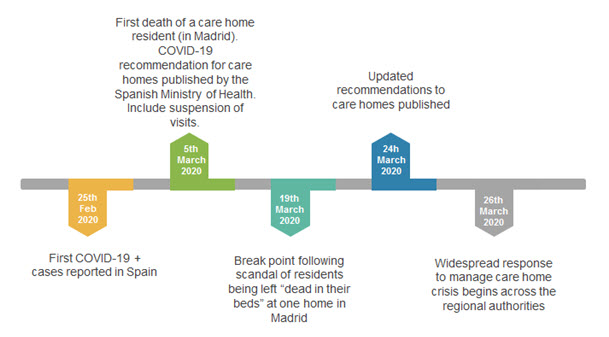

Among the factors that might be relevant, one is the speed at which the virus spread across the country, which affected the ability of authorities to respond in a timely manner. COVID-19 cases were reported in almost every region in Spain within only five days of the first recorded cases (25th February 2020 in Madrid, Valencia and Catalonia). This was 9 days before the initial set of recommendations for care homes[vii] was published, stipulating – among other measures – the limitations of visitors.

The initial set of recommendations required only the isolation of any symptomatic residents or care workers, but – based on the limited evidence base at the time – did not require special measures with potential asymptomatic cases (i.e. residents or staff that had been in close contact with anyone symptomatic), other than general precautionary measures such as hand-washing between each and every contact with a resident, heightened cleaning and disinfection within the home (particularly of frequently used surfaces). Moreover, the guidelines specified that staff presenting with upper respiratory infection symptoms should be assessed by primary care services to determine whether they could remain at work or not.

However, confusing matters, the initial recommendations referred its readers to general documentation pertaining to ‘procedures to be taken in response to cases of coronavirus infection’[viii], and information related to declaring a Coronavirus outbreak to public health which potentially contradicted the initial recommendation specific to care homes.

For example, the former of these stipulates that all probable cases that are hospitalized or meet the criteria for being hospitalised should be tested, as well as all any one with possible symptoms working in health or social care or any essential service. This seemingly left residents presenting with symptoms that were not severe enough to warrant hospitalization outside of the cohort requiring testing, but also implied that staff should be tested as priority.

Moreover the general document on procedures to be taken in response to cases of coronavirus infection also refers to the necessary quarantine of any person (including health and social care staff or family members) that have provided care to anyone categorised as a possible, probable or confirmed case without using “adequate means of protection”, or been at less than 2 metres distance from someone categorised as a possible, probable or confirmed case for 15 minutes or more. Only care home directors of staff that were able to wade through these different documents would have noted that this implied the need for greater precaution than described in the main set of recommendations for care homes.

A further issue is that the initial recommendations for care homes did not specify who to contact in the event of suspected cases, difficulties maintaining staffing levels, lack of personal protective equipment or any of the situations likely to be arising. It should also be noted that care homes in Spain do not benefit from any form of regular contact with the governing administrations that contract places. There are no equivalents to purchaser-provider or commissioning forums and standard setting and regulation is exerted in an extremely top-down fashion. Unsurprisingly then, at the start of the outbreak no unique contact point was made available to care homes in each region. As a result care homes have were calling the general telephone number for health emergencies in Spain (112) to report potential infections and responding to advice given by staff that were not specifically trained to assess the vulnerabilities and needs of care homes.

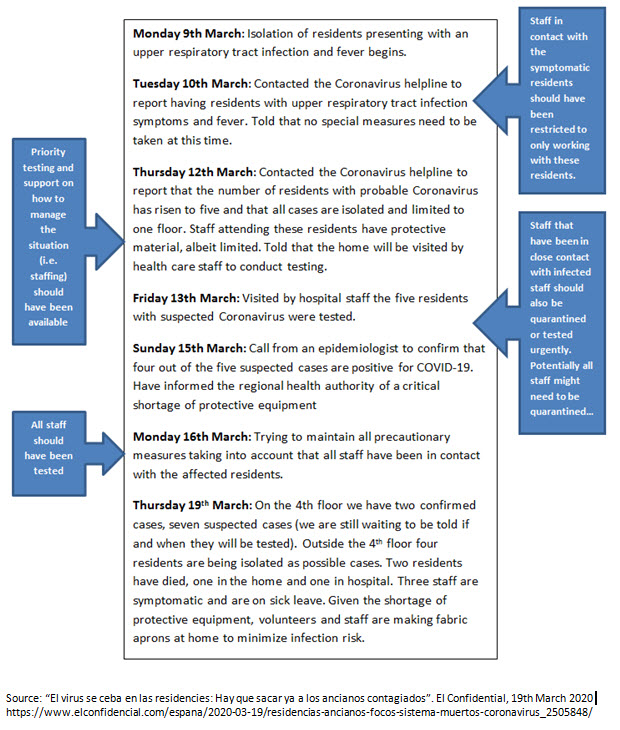

Other important factors such as lack of personal protective equipment, the low priority given to symptomatic residents for hospitalization and lack of medical support have also been heightened because care homes have not had a clear and unique route through which to communicate their difficulties. Even if such a route had existed, there were no protocols in place to facilitate the extent of support that rapidly became necessary, particularly in terms of replacing staff (such as mobilizing staff from day centres to care homes) and no clear definition of who should be responsible for ensuring that care homes could maintain staffing levels or providing other solutions. All this sowed the seeds for a perfect storm illustrated by the diary entries from a care home director in Madrid (reported in El Confidential, 19th March 2020). My superficial analysis of the reporting highlights some of the obvious downfalls (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Analysis of reported diary entries from a care home director in Madrid

In response to worldwide coverage of the situation affecting care homes in Spain, things have now shifted, some two and a half weeks since the first coronavirus related death of a care home resident.

Figure 3: Evolution of the COVID-19 care home crisis in Spain

On the 22nd March, the government announced that care homes unable to report minimum standards “must report to the competent authorities in their region”[ix], even if many argued that they had been doing so for days. Updated recommendations for care homes were published on the 24th March[x] and in these precautionary measures to minimize contagion in care homes are now focused on all possible, probable and confirmed cases therefore extending isolation measures to some residents who are asymptomatic. Measures for staff are similar.

The problem is that almost as soon as residents and staff start to become symptomatic the challenge to maintain adequate staffing, implement full precautionary measures and ultimately maintain basic standards of care rises exponentially and very quickly becomes impossible (see Figure 2). Many care homes are now reporting that if they applied these measures they would have to send all staff members home. Other staff members are now “too afraid” to come to work. On top of it, there are reports of cracks in the supply chain to care homes, including refusal to deliver incontinence pads[xi]

As described in this blog[xii], action is now being taken to mobilise external available care staff and volunteers, transfer some asymptomatic residents to be cared for in hotels[xiii], and allow families the option of bringing their relative home without losing their place. However these measures have only materialized in the last couple of days and it is too late for the dead, not to mention the care residents that remain COVID-19 positive.

Among the many thoughts that weigh heavily at this time is the notion that this can, and will, happen again and again, in different countries. Hopefully a number of lessons can be taken from this post. The necessity for clear lines of communication and proactive organisation of radical response measures must be emphasised.

Suggested citation:

Davey V (2020) Report: The COVID-19 crisis in care homes in Spain, recipe for a perfect storm. Article in LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE.

[i] https://www.ft.com/coronavirus-latest

[ii] de Marti, J. (2019) “Trabaja suficiente personal en las residencias”. Available online at: https://dependencia.info/noticia/2430/opinion/trabaja-suficiente-personal-en-las-residencias.html

[iii] CBRE (2018) Residencias para la Tercera Edad. Teaser de Mercado. Available online at: https://www.cbre.es/es-es/research-and-reports/residencias-tercera-edad

[iv] Ibid.

[v] “Más de mil ancianos de residencias madrileñas han muerto desde que comenzó la crisis del coronavirus”, 20 Minutos. Available at: https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/4206610/0/mas-mil-muertos-residencias-mayores-crisis-coronavirus/

[vi] Mitnitski, A., Song, X., Skoog, I., Broe, G., Cox, J. L., Grunfeld, E., & Rockwood, K. (2005). Relative Fitness and Frailty of Elderly Men and Women in Developed Countries and Their Relationship with Mortality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(12), 2184–2189.

[vii] Spanish Health Ministry (2020) Recomendaciones a residencias de mayores y centros sociosanitarios para elCOVID-19. Documento técnico. Versión de 5 de marzo de 2020. Available at: https://www.segg.es/actualidad-segg/2020/03/06/recomendaciones-a-residencias-de-mayores-y-centros-sociosanitarios-covid-19

[viii] “Procedimiento de Actuación frente a casos de infección por el Nuevo coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)”. Spanish Ministry of Health, versión 15 de marzo de 2020 https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Procedimiento_COVID_19.pdf

[ix] https://twitter.com/desdelamoncloa/status/1241709751081349120

[x] Spanish Health Ministry (2020)

Guía de prevención y control frente al COVID-19 en residencias de mayores y otros centros de servicios sociales de carácter residencial. Versión de 24 de marzo de 2020. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Residencias_y_centros_sociosanitarios_COVID-19.pdf

[xi] de Marti, J. (2020) Reflexiona sobre residencias y coronavirus. Available at: https://dependencia.info/noticia/3392/visto-en-la-red/canal-inforesidencias.com:-josep-de-marti-reflexiona-sobre-residencias-y-coronavirus.html

[xii] Comas-Herrera (2020) Tackling COVID-19 outbreaks and staff shortages in care homes: deploying rapid response teams. Article in LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE.

[xiii] “Cataluña autoriza que las familias se llevan a casa a sus mayores no contagiados de las residencias sin perder la plaza.” Antenna 3, 26th March 2020. https://www.antena3.com/noticias/sociedad/cataluna-autoriza-que-familias-lleven-casa-sus-mayores-contagiados-residencias-perder-plaza_202003265e7cb38c4626fc0001c3c6a1.html

Pingback: COVID-19 i cures de llarga durada a Espanya: impacte, causes i primeres mesures | Lleiengel.cat

Pingback: La urgencia de cambiar el modelo de residencias para mayores - Agenda Pública