By: Dr Sarah House and Eric Fewster

Building on previous analysis of IPC guidance and the history of asymptomatic transmission

In early April 2020 we undertook analysis on the UK Government infection, prevention and control (IPC) guidance for care homes. We identified significant gaps in the guidance, which we found to be weak, scattered, difficult to access, and some of it contradictory, or with factual errors. In particular, we identified the lack of focus on asymptomatic transmission, as a significant weakness.

Subsequently we worked with inputs from a wider group of cross-sectoral specialists to develop an interim IPC strategy that care homes could use, while working to try and influence to the UK Government to respond to the gaps. The first version went online on 18 April, and there have been several iterations of the document since then. The holding page of the document is here: https://www.bushproof.com/care-homes-strategy-for-infection-prevention-control-of-covid-19-based-on-clear-delineation-of-risk-zones/

As part of this process we also undertook a more detailed analysis of the UK Govt / England’s IPC guidance (15 May): https://ltccovid.org/2020/05/15/mapping-of-uk-government-guidance-for-infection-prevention-and-control-ipc-for-covid-19-in-care-homes/ and also later we undertook analysis of progress in responding to asymptomatic transmission (12 June): https://ltccovid.org/2020/06/12/asymptomatic-and-pre-symptomatic-transmission-in-uk-care-homes-and-infection-prevention-and-control-ipc-guidance-an-update/

Despite its importance, it took a long time for much of the scientific community, some governments and international organizations to recognize it. This article in the New York Times by Kirkpatrick, D. on 27 June 2020, highlights what happened well: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/27/world/europe/coronavirus-spread-asymptomatic.html#click=https://t.co/EsRkNGOK0i

As the article by Kirkpatrick, highlights there were already case studies emerging of asymptomatic cases and transmission from January/February onwards. The UK scientific advisory bodies, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and the New and Emerging Respiratory Viruses Technical Advisory Group (NERVTAG), Public Health England (PHE) and the UK Department of Health and Social Care, discussed this issue regularly from January onwards, but rather than taking the precautionary principle, chose to base their strategic responses only on symptomatic transmission. It was not until late-May 2020 that the UK Government started to talk about asymptomatic transmission openly and not until 16 June that it was integrated to some degree into theiradmission and care of residents document for care homes during the COVID-19 outbreak.

In this post we would like to provide an overview of the factors that, from an infection prevention and control perspective, we feel may have contributed to the high numbers of deaths in UK care homes, and then to look more specifically at:

- Why taking so long to incorporate asymptomatic transmission evidence in the guidance and policies, was a significant part of the problem.

- Why it is so important to have clear and practical IPC guidance for care homes, because undertaking effective IPC for Covid-19 is challenging due to the wide variation in contexts and set-ups of care homes and when supporting people with high care needs.

Potential contributing factors to the high numbers of deaths in UK care homes

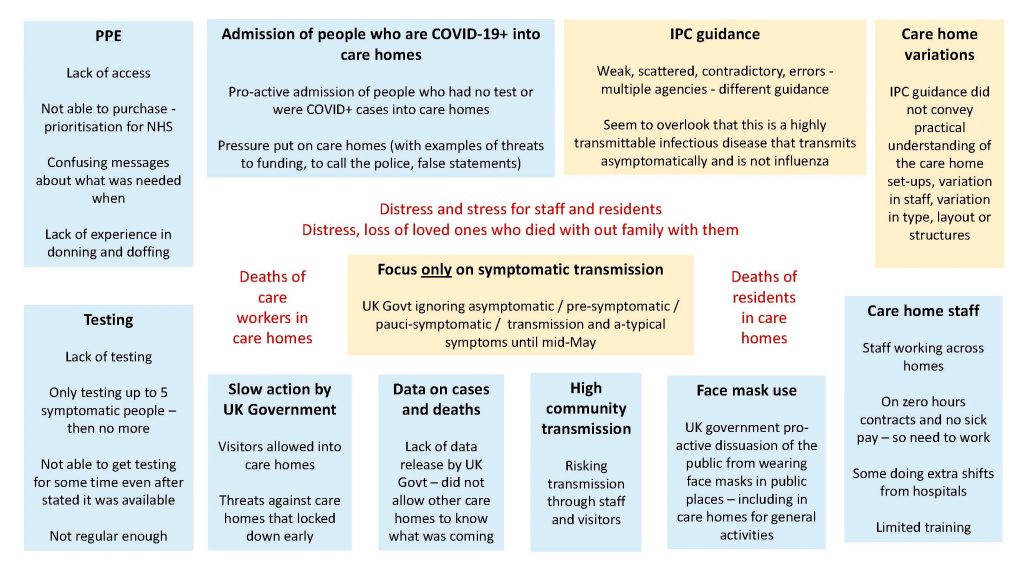

Figure 1 provides an overview of the factors that we believe may have contributed to the high numbers of deaths of residents and staff in UK care homes. Some of these factors (blue boxes) have over the past few months slowly been picked up often first by the UK media and following this, by the UK government in its daily briefings. For some, actions have been taken to remedy the problem.

Potential contributing factors high number of deaths that have had more attention in the media and have been discussed more by the UK Government and media:

- UK Government / Public Health England not releasing the data on care home infections and deaths for several months

- Pro-active admission of residents from hospitals into care homes with no test or who are COVID positive

- Care home staff – working across homes, some on zero-hours contracts without sick pay, some working in hospitals and care homes and with limited training

- Government policy on persuading the public to not wear face masks in public places

- Challenges with accessing PPE and knowing how to put it on and take it off

- Slow action by the government in still permitting visitors and not locking down

- Lack of access to regular and fast testing for staff and residents

- High community transmission – risking transmission through staff and visitors

But there are other important potential contributing factors that have had less attention (yellow boxes), such as the significant gaps in the quality and accessibility of the UK IPC guidance for care homes and the lack of focus on asymptomatic transmission in care homes.

Contributing factors that have not gained as much attention in the UK media or by the UK Government:

- A focus only on symptomatic transmission for the initial months

- Weak, scattered, contradictory and sometimes incorrect infection prevention and control (IPC) guidance

- IPC guidance that does not recognise the wide variation in different kinds of care home and building set-ups and the challenges for IPC related to caring for people living with dementia

Figure 1. Overview of potential contributing factors to high levels of death of residents and staff in UK care homes

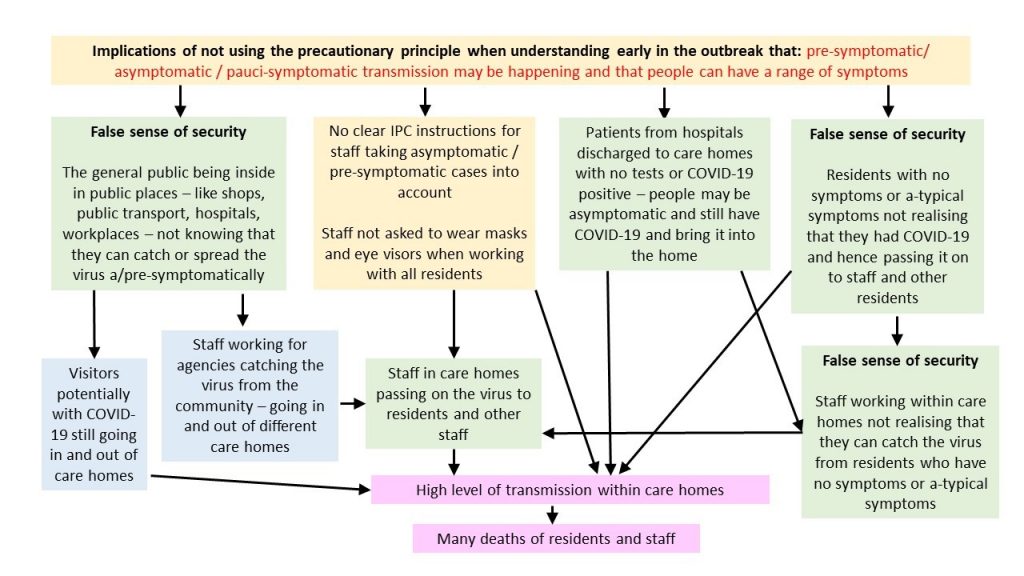

Figure 2 provides an overview of what we believe are probably the consequences for care homes of not taking the precautionary principle for IPC related to asymptomatic / pre-symptomatic / pauci-symptomatic transmission and not recognising a-typical symptoms, which are more common for older people.

Figure 2. Potential implications of not using the precautionary principle for a- and pre-symptomatic transmission

Why care homes face challenge for implementing Infection and Control

Care homes in the UK face important challenges to implement IPC for a number of reasons that relate to their wide variation in type, size, layout, age of buildings, staffing and some of the characteristics of the residents who live in the homes.

Here we summarise some of the challenges, some of which we were aware of when we started working on the IPC strategy and others that became apparent though our direct engagement with care home managers and networks.

Because of the complexity of the care home environment, staffing and the residents who tend to live in care homes, it is essential that IPC guidance is:

- Simple, clear and easy to understand and communicate

- Adaptable to different contexts and to the different needs of the residents

- Helps the management visualise the whole home and consider the potential transmission routes for the disease and the possible barriers that can be put in place

Examples of the complexity of the care home set-up and the features of why care homes are challenging for IPC:

A – Variation in types of home and residents

- Homes are varied in type – for example, they may include residential care homes, nursing homes, sheltered housing, group homes

- Some are managed as a chain of care homes by large companies, and others are owned and managed by individual owners

- Some may support older people and adults or children with disabilities and including people with mental health conditions

- It is understood that around 85% of older people in care homes in the UK have dementia

B – Physical set up of homes

- Sizes of the care homes vary significantly – from single terraced house buildings to complexes with multiple buildings and hundreds of residents

- Smaller homes may find IPC more difficult – they may struggle more to zone the home into separate areas to isolate people who are confirmed or suspected of having COVID

- Some buildings have been converted from older buildings, some are newer structures

- Wide variety of layouts – which means it will be critical for the care home manager to be able to adapt guidance and consider the transmission risks and possible barriers for their particular layout

- May have long and sometimes narrow corridors or networks of corridors – restricting what can be placed in the corridors (for example small tables for hand gel) as it may pose a fire hazard

C – Physical aspects posing challenges for implementing hygiene procedures

- Care homes are homes where people live, and are not the same as hospitals where most people tend to go for a short period of time – this means that there are communal areas for companionship, activities, entertainment and meals

- Care home rooms are the person’s home and tend to have all of their personal possessions around the room, including pictures on walls, trinkets and other items – which makes it difficult to move residents between rooms for purposes of isolation, unless you have an empty room they can stay in temporarily.

- Communal areas – mean that people are together in groups with movement of staff and residents

- Many have carpets and a range of soft furnishings which are difficult to clean and may need vacuuming – which may cause risks with aerosols and means that you are not able to simply mop and disinfect floors

- Not all bedrooms may have a sink – making it difficult for hand-washing whilst providing care

- Not all bedrooms have their own toilet and shower – making it more difficult to isolate residents and contain the virus away from communal toilet/shower facilities and areas

D – Residents living with dementia

- Residents who have dementia and are mobile – may ‘walk with purpose’, where they like to walk around the building or out of the home – this can result in the following challenges:

- It can be difficult to isolate them in their rooms (in the UK care homes do not lock people in their rooms)

- It can be difficult to stop them walking into the rooms of other residents

- They may approach and want to touch or hug the care-workers

- It may be difficult for them to wear masks

- Some people who have dementia can also get quite disturbed and upset or angry quite quickly – they may need calming down with touch from the carer such as putting their arm around the person

- They may not understand the rules of behaviour during the outbreak to reduce the risk of transmission and the staff wearing masks and other protective equipment may be distressing for them

E – Residents living with physical and sensory difficulties

- Staff often have to provide intimate care for residents who are less mobile, including changing clothes and incontinence pads – posing risks from closeness and handling of soiled items

- Staff may have to handle residents when lifting them from laying to seated position, turning them over, moving them from bed to commode or toilet and for other purposes – posing risks from closeness and risk having PPE pulled off them

- Residents who have difficulty hearing or seeing may need the staff to come close to their faces / ears – so as to be able to see or hear them properly

- Older people who cannot hear well may rely to some degree on lip reading – which then is constrained when staff wear masks

F – Visitors, end of life care and impacts of isolation

- As many people living in care homes may be in the final years of their lives, having company and visitors is likely to be particularly important – so restricting visitors can be particularly distressing and have a negative impact on the mental health of both the residents and the family members

- It can be difficult to know how to allow visitors to have contact with their relatives or friends – without the risks of transmission to the residents in the home

- Older residents need to keep moving to prevent muscle loss – so isolating them in their rooms for long periods of time can have significant implications on their general health and can lead to physical deterioration

G – Staff and training

- Smaller homes will have less staff – both care staff and cleaning and other support staff – and hence will be difficult to cohort staff to only work in confirmed (red), suspected (amber), or other (green) areas

- There may be a high turnover of staff and use of agency staff to fill gaps – including when staff have to themselves self-isolate

- Hence it will be very difficult to train staff who come in new each day in all of the IPC procedures for that particular home with that particular layout – particularly where the IPC procedures are not clear and hence care managers are having to adapt and develop their own, as has been the case with this outbreak

- Most staff do not have a nursing background – and hence many will not have had IPC training prior to working in a care home environment

- Some staff may not have a high level of education and some may only have basic reading skills, and others may not be strong in English as it may be their second or third language – meaning that any IPC guidance instructions must be easy to understand and remember through verbal training

- There will be a need for repeat training for all staff – to prevent standards slipping over time and also to respond to the turnover of staff

H – Staff becoming infected

- Staff are often on low-paid contracts or salaries and more likely to use public transport – putting them more at risk of contracting COVID-19 from other commuters

- Staff may be on zero hours contracts which means they do not get paid when they do not work– which may lead them to hiding minor symptoms if they are not well

- Agency staff often work across homes– so can pass the infections from one home to another, particularly if they are asymptomatic and do not know they are COVID+

- Nursing staff working for agencies may be doing additional shifts outside of their regular hospital-based work – hence risking bringing in infections from the hospital environment

Detailed analysis of what was known by the UK Govt advisory bodies when and timeline for focus on care homes

In July the UK Government and the Secretary of State for Social Care have been noting in the media that the reason for the high number of deaths in UK care homes, was because they did not know about asymptomatic transmission. From our analysis of the SAGE and NERVTAG minutes, this was clearly not the case, as the scientific advisors and the UK Government were discussing emerging case studies and evidence on this issue since January 2020.

For further information and more detailed analysis and a detailed timeline of what was known when, in relation to asymptomatic transmission and also how much the UK Government advisory bodies prioritised discussions on the needs of people in care homes during the Covid-19 pandemic – see here: https://www.bushproof.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Gaps-UK-Govt-IPC-care-homesasymptomatic-13_7_20-FINAL-upload.pdf.