David Bell, University of Stirling

Delayed discharges occur when a hospital patient considered well enough to return to the wider community continues to occupy a hospital bed because of difficulties in accessing the necessary care, support or accommodation. Such delays are generally not in patients’ best interest since most would prefer to leave hospital – extended stays in hospital are generally harmful to patient wellbeing. Delays are not in the interest of the healthcare system either because they reduce patient throughput. They are also expensive: the average cost of an inpatient week across Scottish hospitals in 2018/19 was £4702[1]. Having someone occupy a bed for no clinical reason implies resources are not being used efficiently.

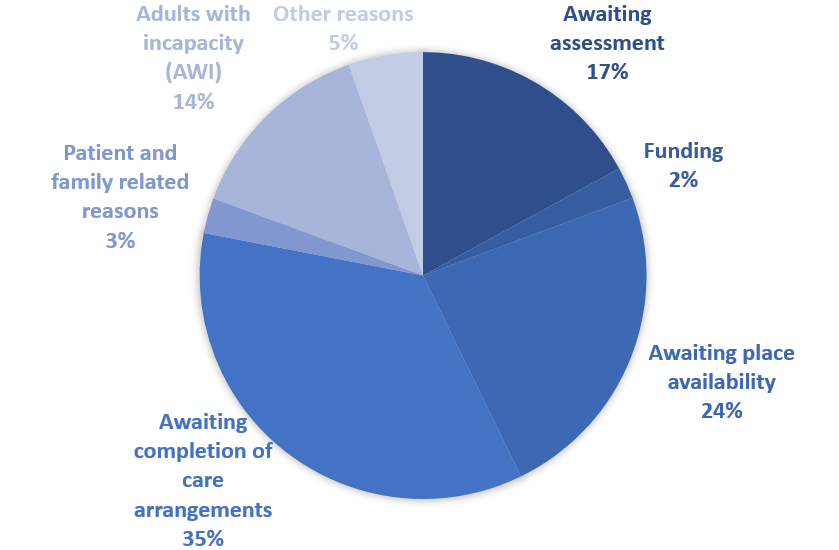

This issue has been a long-term concern for governments across the UK and has led to collection of detailed statistics so that the problem can be better understood. In Scotland, consistent data, based on a monthly census, have been available since July 2016. Data definitions were changed at that time partly to reflect the newly established Health and Social Partnerships and, in particular, a desire to eliminate differences between “health reasons” and “social work” reasons for delayed discharges. Each delayed discharge is now assessed and categorised. Delays fall into three main categories – those associated with health and social arrangements, those caused by arrangements relating to the patient, family or carer and more complex reasons relating to the specific care needs of the person. A more detailed breakdown is shown in Figure 1 which shows the share of each type of delay in total delayed discharges during 2019/20.

Figure 1: Reasons for Delay 2019/20

Source: Public Health Scotland

Delays caused by health and social arrangements dominate. Specifically, waiting for assessments, setting up care arrangements, arranging funding and waiting for availability of places make up 78% of all delays. Although no age breakdown is available, these arrangements will largely apply to older people who are likely to have greater need for appropriate care arrangements.

Public Health Scotland has recently released monthly data covering the period up to and including March 2020. These show a remarkable turnaround between February and March 2020. The number of delayed discharges fell from 1627 to 1171 during this period, an overall reduction of 28%. The principal reason for reductions in delayed discharge, accounting for 98% of the total, was “health and social care reasons”, suggesting that Scottish Health and Social Partnerships increased the volume of assessments, placements and care arrangements so that a substantial number of older people whose discharge had been delayed, could be moved into the community or care homes. This was likely associated with a desire to remove patients who were potentially vulnerable to COVID19 away from hospital settings.

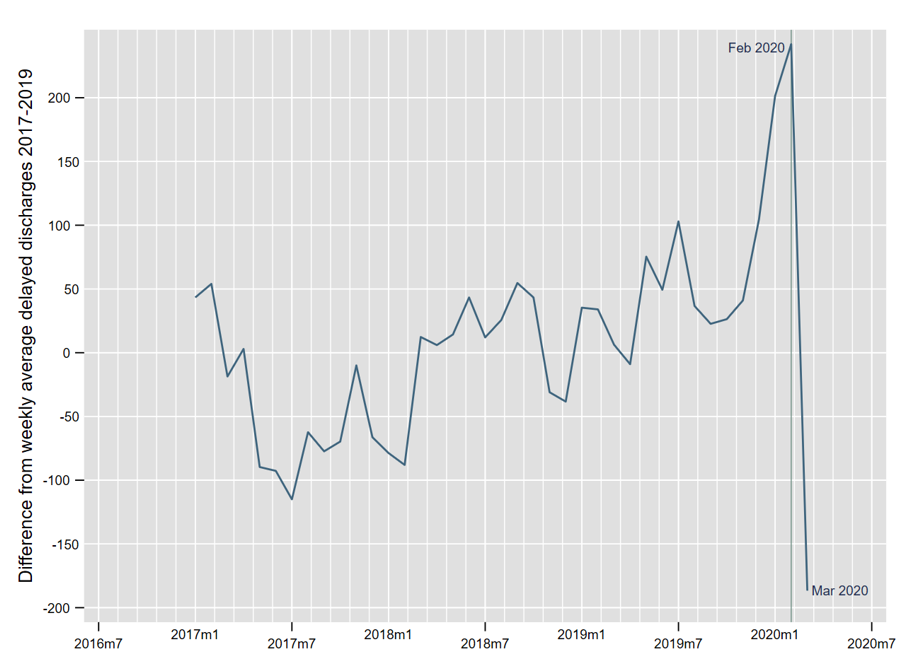

Figure 2 shows how far the pattern of delayed discharges in 2020 deviated from recent experience. It shows the difference between actual delayed discharges and mean monthly discharges over the period 2017-2019. What is evident is a gradual upward trend in delayed discharges from mid-2017 onward, a marked rise during January and February 2020 and then an even more marked decline during March.

Figure 2: “Excess” Delayed Discharges – Difference between actual delayed discharges 2017-2020 and mean delayed discharges between 2017 and 2019

Source: Public Health Scotland and Own Calculations

These data provide clear evidence of the imperative to clear hospitals prior to the pandemic. Those moved away from hospital will have been accommodated in care homes or in a domestic setting. It is likely that these arrangements were made in haste with probably the laudable motive of protecting patients from the virus. Whether this process has caused more problems by placing some people with COVID infections in settings where they could infect others or by exposing frail individuals to more risk than they would have faced in hospital must await further research. This should be feasible, given that all delayed discharge records can be attached to the Scottish Community Health Index data spine. Some qualitative information (Oliver 2020)[2] suggests that communication between general hospitals and intermediate care (including requisitioned hotels) improved markedly: assessments were done more rapidly and delays in transfers between hospital and care homes fell sharply. Failures included not testing those discharged to care homes; not considering how well-equipped care homes were to deal with residents who were potentially carriers of COVID-19 and not understanding the challenges facing care home staff.

[1] Source: Scottish Government, Information Services Division, hospital costs data 2018/19.

[2] HSJ (2020) “What went wrong (and right) in hospital discharge for older adults during the pandemic”, May, Accessed at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/frail-older-people/what-went-wrong-and-right-in-hospital-discharge-for-older-adults-during-the-pandemic/7027710.article?adredir=1 on May 27.